Parke’s Castle

July 10, 2025 2025-07-10 17:11Parke’s Castle

Parke’s Castle

A Leitrim Stronghold Echoing O’Dubhda History

A Sentinel of Shared Heritage on Lough Gill

Parke’s Castle, majestically situated on the shores of Lough Gill in County Leitrim, stands as a profound testament to the layered tapestry of Irish history. While widely recognized as a stronghold of the O’Rourke clan and later an English plantation manor, its story is deeply intertwined with the broader narrative of Gaelic Ireland. For the O’Dubhda clan, whose ancestral lands and influence stretched across much of Northwest Connacht, Parke’s Castle represents a significant landmark within a historical landscape that the clan’s forebears knew intimately. This page explores the castle’s storied past, its architectural evolution, and its enduring connection to the rich heritage of clans such as the Ó Dubhda.

I. Overview: Journey Through Time at Parke’s Castle

Parke’s Castle is a beautifully restored 17th-century fortified manor house located on the tranquil shores of Lough Gill in Kilmore Fivemilebourne, County Leitrim. Its picturesque setting makes it a captivating site for visitors, offering a tangible glimpse into centuries of Irish history. The castle is often referred to as a “plantation castle,” having been built by Captain Robert Parke. However, it is crucial to note that it stands on the foundations of an earlier 15th or 16th-century tower house that belonged to the powerful O’Rourke clan, who were rulers of Breifne. This dual history, encompassing both Gaelic and Plantation eras, is central to understanding the site’s profound significance.

The O’Dubhda clan, known as Ó Dubhda in its original Irish form, possesses a lineage stretching back over 1500 years, with the surname itself being one of the oldest in Europe, first used by Aedh Ua Dubhda in 982 AD. The ancestral homeland of the O’Dubhda clan encompassed significant portions of modern-day County Mayo and County Sligo, particularly the baronies of Erris, Tirawley, and Tireragh. This territory, known as Uí Fiachrach Muaidhe, bordered the O’Rourke lands of Breifne, creating a shared historical and geographical sphere of influence. The presence of both the O’Dubhda and O’Rourke clans in adjacent regions, particularly with the O’Dubhda clan having a documented fortified presence on Lough Gill itself, indicates that this significant body of water was a shared strategic and cultural landscape. This suggests a history of potential interaction, competition, or alliance between these prominent Gaelic families over its control or access, making the story of Parke’s Castle relevant to the broader O’Dubhda narrative.

II. The Storied Past: Parke’s Castle Through the Ages

The history of Parke’s Castle serves as a microcosm of the profound shifts in Irish power dynamics, transitioning from a Gaelic stronghold to a symbol of English colonial expansion. This narrative arc reflects the broader challenges and transformations faced by all Gaelic clans, including the O’Dubhda.

A. The O’Rourke Stronghold: Newtown Castle

The site of Parke’s Castle was originally home to a 15th or 16th-century O’Rourke tower house, known as Newtown Castle. This earlier structure received mention in the Annals of Lough Cé in 1546. Sir Brian O’Rourke, Lord of West Breifne from 1566, was a prominent figure associated with this stronghold. His rule was marked by significant resistance to English Crown authority. In a defiant act to prevent English occupation, Sir Brian even dismantled his own castles at Leitrim, Newtown (the future Parke’s Castle site), and Dromahair in 1580.

A pivotal moment in Sir Brian O’Rourke’s relationship with the Elizabethan regime occurred in 1588 when he sheltered approximately eighty survivors of the Spanish Armada shipwrecked at Streedagh beach in Sligo. This humanitarian act was deemed an act of high treason by the English Crown. Consequently, Sir Brian O’Rourke was arrested, becoming the subject of the first recorded extradition case in Ireland and Britain. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London and subsequently found guilty of high treason without legal representation or the opportunity to examine the charges against him. On November 3, 1591, he was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn. Following his execution, his lands, including Newtown Castle, were confiscated by the English Crown. His son, Brian Óg O’Rourke, continued the struggle against the English, participating in the Nine Years’ War.

B. The Plantation Era: Captain Parke’s Transformation

The confiscation of O’Rourke’s lands marked the beginning of the Plantation of Leitrim, a systematic English policy initiated around 1620 to dispossess native Irish lords and settle loyal English and Scottish planters. The site of Newtown Castle was eventually acquired by Captain Robert Parke. Captain Parke subsequently built the current fortified manor house, which is known today as Parke’s Castle, largely between 1628 and the mid-1630s. He utilized the stones and foundations of the demolished O’Rourke tower house for this new construction, a symbolic act of replacement and assertion of new authority. The castle, therefore, stands as a prime example of a “plantation fortified house”.

Robert Parke prospered under the new regime, even serving as High Sheriff of Leitrim. However, the Parke family also faced tragedy; local accounts suggest two of Parke’s children drowned in Lough Gill in 1677. Following this, or perhaps due to other factors, the castle subsequently fell into disrepair.

C. Restoration and Enduring Legacy

By 1791, historical drawings depicted Parke’s Castle in a ruinous state, and it remained uninhabited for nearly two centuries. During this period, the bawn, or defensive courtyard, was utilized as a farmyard and stables until the early 20th century. The Irish Free State acquired the site in 1935, placing it under State care. Extensive archaeological excavations were conducted in the early 1970s, paving the way for a meticulous restoration by the Office of Public Works (OPW). This restoration employed traditional Irish oak and craftsmanship, reviving the castle to its 17th-century appearance. This careful work has transformed Parke’s Castle into a significant educational and tourist attraction, allowing visitors to engage with its rich history.

III. Architectural Marvels: Unveiling Parke’s Castle’s Design

The physical structure of Parke’s Castle provides a tangible record of its layered history, showcasing the transition from ancient Gaelic defenses to a 17th-century Plantation manor. The architectural evolution of the site visually represents the historical forces that shaped the destinies of Irish clans.

A. Echoes of Gaelic Defenses: The O’Rourke Foundations

During archaeological excavations in the early 1970s, the foundations of the original O’Rourke tower house were discovered beneath the cobblestones of the current courtyard. This discovery confirmed the site’s deeper Gaelic roots and its prior existence as Newtown Castle. The O’Rourke tower house, likely constructed in the mid-15th century, was part of a more extensive defensive complex that included a bawn and a rock-cut ditch or moat. This earlier structure was systematically demolished down to its foundations by Captain Parke, signifying a deliberate act of replacing the former Gaelic stronghold with a new colonial structure.

B. A Planter’s Fortification: Parke’s Manor House and Bawn

Captain Robert Parke’s construction transformed the site into the fortified manor house visible today. He notably repurposed the stones from the demolished O’Rourke tower house for this new build. The existing castle largely reflects Parke’s 17th-century design. It features a prominent three-storey gatehouse, which likely served as the initial accommodation for Parke and his family. Two substantial defensive towers were erected in the northwest and northeast corners, complemented by smaller sentry towers and a sally port (water gate) on the southern wall. The bawn walls were reinforced and modernized with the addition of gun loops and crenellations, enhancing their defensive capabilities. The interior courtyard was paved with cobblestone, a deliberate act that effectively removed visible traces of the earlier Gaelic castle. Other notable features include a dovecote, a well house, and various outbuildings.

C. Traditional Craftsmanship: The Restored Structure

The Office of Public Works undertook a meticulous restoration of the castle, employing traditional craftsmanship and authentic materials. This included the use of Irish oak for the roof, constructed using the mortise and tenon technique, a testament to 17th-century building methods. The restoration also involved the reconstruction of a blacksmith forge and stables, along with the addition of wainscoting to the upper floors, all contributing to an immersive historical experience for visitors.

IV. The O’Dubhda Presence: Connections to the Lough Gill Landscape

While Parke’s Castle is primarily associated with the O’Rourke family and later Captain Parke, its location within a historically significant landscape, intimately known and fortified by the O’Dubhda clan, establishes a profound connection. The layers of history at Parke’s Castle, from its O’Rourke origins to its Plantation transformation, serve as a powerful symbol of the profound changes that swept across Ireland from the 16th to 17th centuries, embodying the shift from ancient Gaelic lordships to the era of English plantations. This historical trajectory resonates deeply with the experiences of the O’Dubhda clan.

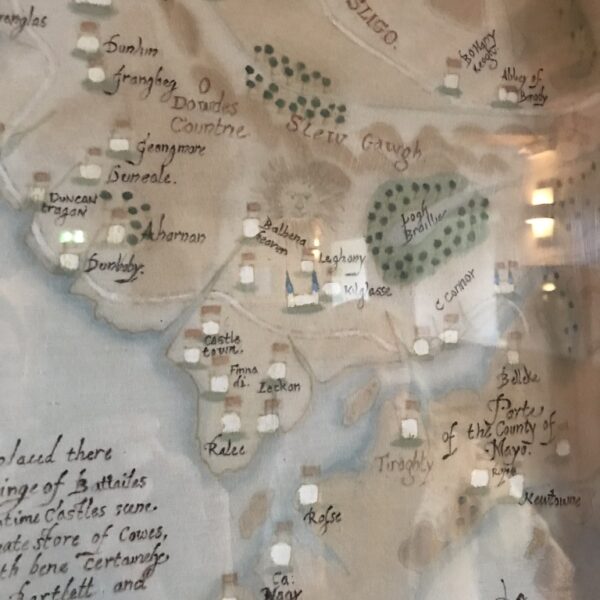

A. The O’Dubhda Clan: Our Ancestral Domain and Identity

The O’Dubhda clan, descended from Fiachrae, brother of Niall of the Nine Hostages, was the leading sept of the northern Uí Fiachrach. The clan’s territory, Uí Fiachrach Muaidhe, at its widest extent, embraced the baronies of Erris and Tirawley in Mayo and Tireragh in Sligo. This extensive domain placed the O’Dubhda clan in close geographical proximity to the O’Rourke lands of Breifne, which included the area around Lough Gill.

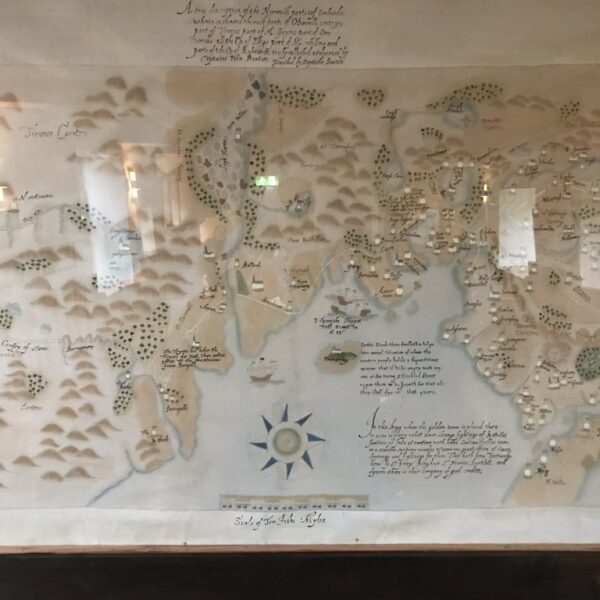

The O’Dubhda clan maintained a formidable network of fortifications, famously described as “20 castles” ringing their territory. These included traditional Gaelic strongholds, adapted Norman castles, and purpose-built tower houses. Significantly, historical research has identified “Lough Gill” as one of these 20 O’Dubhda castles. This confirms a direct, fortified presence of the O’Dubhda clan on or immediately adjacent to Lough Gill, the very lake where Parke’s Castle stands. This demonstrates the O’Dubhda clan’s historical influence and strategic presence in the immediate vicinity of this significant landmark.

The O’Dubhda clan was also notable patrons of the MacFirbis clan, hereditary chroniclers who produced vital works of Irish history such as the Great Book of Lecan and Leabhar na nGenealach. These meticulously kept records preserve not only the O’Dubhda clan’s own history and inauguration ceremonies but also provide invaluable context for the wider historical landscape, including interactions with neighboring powers.

B. Intertwined Histories: O’Dubhda and O’Rourke Interactions

Both the O’Dubhda and O’Rourke clans were prominent Gaelic families in Connacht, sharing a common ancestry from the Connachta’s Uí Fiachrach and Uí Briúin respectively. Their histories were frequently intertwined through alliances, rivalries, and shared resistance against external forces, particularly the Anglo-Normans and later the English Crown.

The O’Dubhda clan’s strong presence in Sligo and Mayo meant that their territories bordered or were in close proximity to the O’Rourkes’ lands. The O’Dubhda’s demonstrated ability to “hold their territory intact against the superior forces of the Burkes and Birminghams” indicates their active role in the regional power struggles that would have involved all powerful clans, including the O’Rourkes. If Lough Gill was a strategic and economic hub, and the O’Dubhda clan had a castle on Lough Gill, it implies that both clans likely had an interest in and potentially contested or cooperated over the control and use of this vital waterway and its resources.

Furthermore, both clans were significantly impacted by and participated in the broader conflicts against English expansion. Brian Óg O’Rourke, son of Sir Brian, was involved in the Nine Years’ War and was an important ally of Hugh O’Donnell. Similarly, the O’Dubhda clan played an honorable role in this war, assisting Hugh Roe O’Donnell in defending Ulster’s western border. This shared struggle against a common adversary highlights a significant, albeit indirect, connection, as both clans faced similar pressures and outcomes during this tumultuous period. The fate of Brian O’Rourke—his execution and the confiscation of his lands—and the subsequent Plantation of Leitrim are specific examples of English policy that mirrored the experiences of the O’Dubhda clan, who also saw a rapid decline in power and loss of ancestral possessions after the Irish defeat in 1603 and the Cromwellian re-conquest. This parallel decline, despite their respective strengths, underscores a common cause: the systematic English efforts to assert control over Ireland.

C. A Shared Legacy: The Enduring Spirit of Gaelic Ireland

Parke’s Castle, with its layers of O’Rourke and Parke construction, stands as a powerful symbol of the profound transformations that swept across Ireland from the 16th to 17th centuries. It embodies the shift from ancient Gaelic lordships to the era of English plantations. For the O’Dubhda clan, this castle, situated within a landscape the clan’s ancestors knew and fortified, serves as a tangible link to a shared past of resistance, adaptation, and enduring heritage. It reminds the clan of the strength of Gaelic culture and the resilience of families like the O’Dubhda and O’Rourke in the face of immense change. The stories of these castles, whether those of the O’Dubhda’s own network or those of neighboring clans, are integral to understanding the full narrative of Gaelic Ireland.

V. Visiting Parke’s Castle Today: A Glimpse into a Shared Past

Parke’s Castle today offers a unique opportunity to connect with this rich and complex history. Its restoration and status as a public heritage site make it an accessible point for historical education and reflection.

A. Location & Access

Parke’s Castle is situated on the R286, approximately 11 km from Sligo Town and 7 km from Dromahair, in Kilmore, Fivemilebourne, County Leitrim. The castle is managed by the Office of Public Works (OPW) and is open seasonally, typically from March to November, with daily opening hours. Last admission is usually 45 minutes before closing. A small admission fee is typically charged for adults and children, and guided tours are highly recommended for a comprehensive understanding of the castle’s history. The site offers a large car park, public toilets with disability access, and a tea room during summer months. The ground floor of the castle is wheelchair accessible. An audio-visual presentation and permanent exhibitions of 17th-century artifacts are also available, enhancing the visitor experience.

B. What to Expect

Visitors to Parke’s Castle can expect to explore a beautifully restored 17th-century fortified manor house set in a stunning lakeside location. The guided tour provides valuable insights into the castle’s history, its architectural features, and the lives of its inhabitants across different eras. Highlights include the visible foundations of the earlier O’Rourke tower house in the courtyard, the impressive gatehouse, and the traditional Irish oak roof, meticulously restored using 17th-century techniques. The surrounding area offers beautiful views along Lough Gill, with opportunities for boat tours on the lake. Nearby historical sites such as Creevelea Friary and O’Rourke’s Table can also be explored, further enriching the historical context of the region.

C. Important Considerations

It is advisable for visitors to check opening times and any special event schedules before planning a visit, especially outside peak season. While the castle is well-maintained, visitors should be prepared for varying terrain if exploring the grounds fully. Appreciating the castle’s layered history, from its Gaelic origins to its Plantation transformation, significantly enriches the visitor experience, connecting it to the broader story of Irish clans.

Conclusion

Parke’s Castle, while primarily an O’Rourke stronghold later transformed by English planters, holds a significant place within the broader historical narrative of Gaelic Ireland, particularly for the O’Dubhda clan. The documented presence of O’Dubhda fortifications on Lough Gill itself establishes a direct historical and geographical connection to the castle’s immediate vicinity. The castle’s evolution from a Gaelic tower house to a plantation manor mirrors the widespread dispossession and transformation experienced by many powerful Irish clans, including the O’Dubhda, during centuries of English expansion. Thus, Parke’s Castle stands not merely as a local landmark but as a poignant symbol of shared Gaelic heritage, resilience, and the enduring spirit of a people who shaped the landscape and history of Northwest Connacht. A visit to Parke’s Castle offers a tangible link to this shared past, providing an opportunity for reflection on the profound historical forces that impacted the O’Dubhda clan and their neighboring Gaelic families.

Parke's Castle

Caisleán Pháirc (Parke's Castle)

54°15'52.9"N, 8°20'03.3"W

Kilmore, Fivemilebourne

Sligo, County Leitrim, Ireland

Fortified manor house

Built upon a former Gaelic tower house

c. 1628–1635 (Captain Robert Parke)

Built over a 15th-century O'Rourke tower house

Not destroyed – fully restored

Fell into ruin by the 18th century

Restored by OPW in the 1970s – National Monument

Situated on R286 along Lough Gill

Public heritage site managed by the OPW

Wheelchair accessible ground floor, guided tours available

Daily hours typically 10:00am–6:00pm

Last admission 45 minutes before closing

Located on Lough Gill where O'Dubhda held a documented castle

Contemporary and sometimes rival to O'Rourke clan

Shared historical sphere of influence in Northwest Connacht

Represents Gaelic resistance and transformation during English expansion

Parke’s Castle symbolizes the layered history of Gaelic Ireland, marking the transition from native lordship to colonial rule. With restoration honoring traditional craftsmanship, it offers profound educational insight into the cultural and political shifts that shaped Irish identity.