Ballymote Castle

January 21, 2025 2025-07-09 20:04Ballymote Castle

Ballymote Castle

A Sentinel Witness to Ó Dubhda Resilience

Ballymote Castle, a formidable Anglo-Norman fortress in County Sligo, stands as a silent, yet powerful, testament to centuries of conflict and change in Connacht. While never an Ó Dubhda stronghold, its imposing walls bear witness to pivotal moments in the clan’s history, most notably the audacious act of defiance in 1588 when Ó Dubhda ancestors, alongside allied Gaelic forces, put it to the torch. This is not merely a tale of stone and siege, but a chronicle of the clan’s enduring spirit, resilience, and unwavering commitment to their ancestral lands and sovereignty. This exploration delves into the castle’s storied past through the lens of the Ó Dubhda, a clan whose legacy is deeply etched into the very soil of this historic region.

I. Overview: Journey Through Time at Ballymote Castle

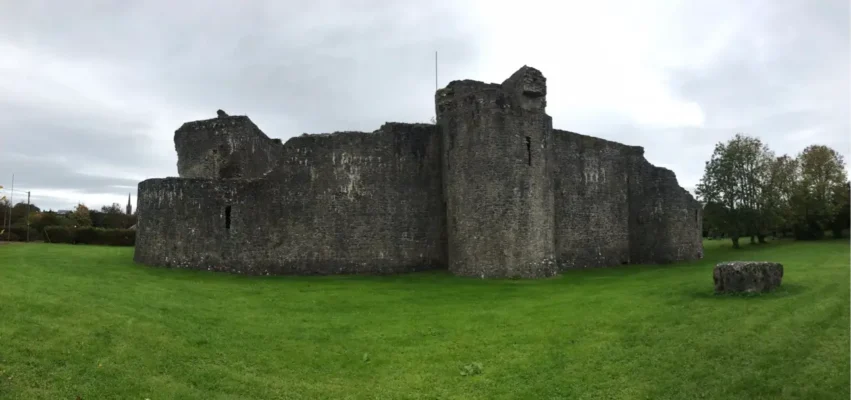

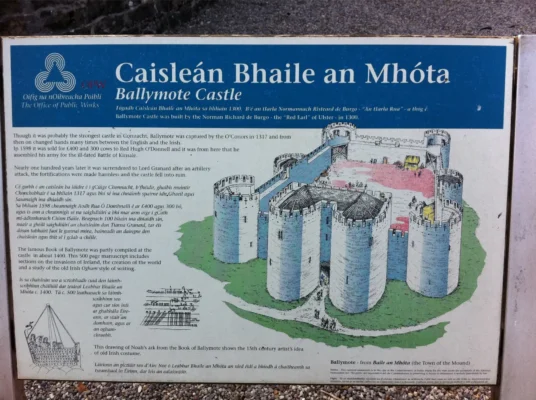

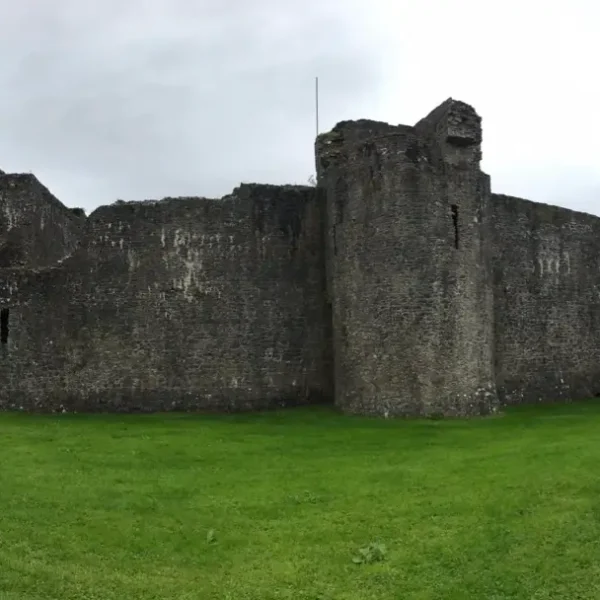

Ballymote Castle, nestled in the market town of Ballymote in County Sligo, Connacht, is an imposing ruin that commands attention. Built around 1300 by the Anglo-Norman Richard de Burgh, the ‘Red Earl’ of Ulster, it was designed to protect his newly acquired possessions in Sligo and was considered the strongest castle in Connacht at the time.1 Its strategic placement made it a coveted prize throughout centuries of Irish history, constantly changing hands between various Irish clans and English forces.1

For the Ó Dubhda clan, whose ancestral lands and influence stretched across what is now County Mayo and County Sligo 5, the rise of such a formidable Anglo-Norman stronghold in their sphere of influence represented a significant challenge. The Uí Fiachrach ancestors, kings of Ui Fiachrach Muaidhe (Northwest Connacht) for centuries 5, were accustomed to holding their territory against external pressures. The construction of this powerful Anglo-Norman fortress in their traditional territory would have been perceived not just as a new building, but as a direct challenge to their long-held sovereignty and influence. It symbolized the encroachment of an external power into lands the clan’s ancestors considered their own, compelling them to adapt their strategies of resistance and survival. The castle’s very existence, therefore, embodies the broader struggle between Gaelic Irish autonomy and Anglo-Norman expansion, a struggle in which the Ó Dubhda clan played an active and enduring role, even if not always as the castle’s direct owner. It highlights the constant pressure and strategic maneuvering required of Gaelic clans to maintain their identity and power.

II. The Storied Past: Ballymote Castle Through the Ages

A. The Red Earl’s Stronghold: A New Power in Ancestral Lands

The year 1300 marked the completion of Ballymote Castle by Richard de Burgh, the ‘Red Earl’ of Ulster.1 This Anglo-Norman magnate, seeking to solidify his control over Sligo, erected a fortress of immense strength, comparable in design to King Edward I’s Beaumaris Castle in Wales.1 Its massive 10-foot-thick walls and formidable gatehouse were clear declarations of power.1

From the perspective of the Ó Dubhda clan, who traced their lineage back to the Kings of Connacht in the 7th and 8th centuries and were the leading sept of the northern Uí Fiachrach 5, the construction of Ballymote Castle represented a significant shift. The clan’s ancestors had long been masters of their domain, even forging a kingdom ringed with their own “10-Pound Castles” to hold off invaders.5 The Red Earl’s imposition of such a stronghold in Connacht was an undeniable challenge to the established Gaelic order and the territorial integrity of clans like the Ó Dubhda. It meant a new, more formidable type of adversary had planted itself firmly in the heart of the clan’s ancestral sphere of influence.

B. A Fortress Contested: Shifting Hands Among the Gaelic Clans

True to the turbulent nature of medieval Ireland, Ballymote Castle rarely remained in one set of hands for long. Just seventeen years after its construction, in 1317, it fell to the O’Connors of Sligo.1 This marked the beginning of a centuries-long saga of changing ownership, reflecting the intense rivalries and power struggles among the Gaelic clans themselves. The Mac Diarmada clan seized it in 1347, followed by the MacDonaghs in 1381.1 For nearly two hundred years, the castle passed back and forth between these powerful Irish families.1

While the Ó Dubhda clan is not explicitly listed as an owner during this period, their presence in County Sligo and Mayo meant they were inextricably linked to these regional conflicts. The clan’s ancestors, known for their maritime power and their ability to hold territory against forces like the Burkes and Birminghams 5, would have keenly observed and strategically navigated these shifts in control. The castle’s constant change of hands among Gaelic lords underscores the dynamic and often violent landscape in which the clan maintained its power and influence. The frequent transfers of ownership among the O’Connors, Mac Diarmada, and MacDonaghs for nearly two centuries illustrate a complex web of alliances, rivalries, and strategic maneuvering that defined the political landscape of Connacht. This demonstrates that the “enemy” was not always solely the English; internal Gaelic politics were equally fierce and vital to survival. The Ó Dubhda’s ability to “hold their territory intact against the superior forces of the Burkes and Birminghams” 5 implies a sophisticated understanding of these regional power plays, including when to ally, when to resist, and when to remain neutral. This reinforces the understanding that Gaelic Ireland was not a monolithic entity but a dynamic system of competing yet interconnected clans, each vying for power and influence, and Ballymote Castle served as a tangible symbol and prize within this intricate system. The Ó Dubhda clan’s survival and influence through these periods speaks to their political acumen and military strength.

C. The Fire of Resistance: Ó Dubhda’s Defiance at Ballymote (1588)

The late 16th century brought a new and more pervasive threat: the full force of the Tudor conquest. Ballymote Castle fell more permanently into English hands in 1584, taken by the notorious Governor of Connacht, Richard Bingham.1 However, the spirit of Gaelic resistance remained unbroken. A pivotal moment, etched into the annals of the clan’s history, occurred just four years later, in 1588, the very year the Spanish Armada arrived off Ireland’s shores. In a defiant act of solidarity and resistance against English occupation, the Ó Dubhda ancestors, alongside the O’Connors and O’Hartes, bravely burned Ballymote Castle.1

This was not a random act of destruction, but a calculated and powerful statement. The burning occurred in 1588, coinciding with the arrival of the Spanish Armada.1 This timing is crucial, suggesting a coordinated effort during a period of heightened Anglo-Irish conflict. Rather than simple vandalism, burning a strategically important fortress like Ballymote (described as the “strongest in Connacht” 1) would have been a deliberate military tactic to deny the English a key stronghold, especially during a potential Spanish invasion or a widespread Irish uprising. This transforms the act from mere rebellion into a sophisticated strategic move by the Gaelic forces, including the Ó Dubhda, to weaken English control and support broader Irish aspirations for sovereignty. For the Ó Dubhda, who had been considerably reduced by earlier Anglo-Norman incursions but had consistently fought to retain their territory and influence 5, this act symbolized an unwavering commitment to Irish sovereignty. It was a testament to the resilience of the clan, demonstrating their readiness to engage in direct action against foreign domination, even when it meant destroying a valuable fortress to deny it to the enemy. This action positions the Ó Dubhda not just as a clan resisting, but as a strategic player in major national conflicts, demonstrating their understanding of military tactics and their commitment to wider Gaelic alliances against the English crown. This event highlights the clan’s active participation in the broader struggle for Irish independence, a struggle that would soon escalate into the Nine Years War, where the clan played an honourable role assisting Hugh Roe O’Donnell.5

D. From Gaelic Aspirations to Cromwellian Ruin: The Castle’s Enduring Legacy

Following the burning, the English surrendered the castle to the MacDonaghs in 1598, who then sold it to the O’Donnells for a substantial sum of £400 and 300 cows.1 It was from Ballymote Castle that the legendary Red Hugh O’Donnell marched to the ill-fated Battle of Kinsale in 1601.1 A year later, the castle, already in a bad state of repair, surrendered to the English.1 Subsequent ownership passed to the Taaffes in 1610/1633 before it was surrendered to Cromwellian forces in 1652.1 This period saw significant upheaval, as the argument between King Charles and his Parliament escalated into open war, prompting the Irish to stage a pre-emptive strike and seize control of various parts of the country. Notably, Tadhg Riabhach O’Dowd was in command of the garrison at Sligo in 1642, and as a Lieutenant-Colonel, he was the officer who surrendered Ballymote Castle to Cromwellian forces in 1652. Following these events, his family settled in areas such as Swinford, Castlebar, Belfast, and Louisburgh, where they have maintained their family tree. The broader political landscape also saw members of the Confederate Catholics, including Edmund O’Dowde of Porterstown and Thady O’Dowde of Rossburr, meeting at Kilkenny in 1646. The subsequent Commonwealth period brought the transplantation of Catholics from across Ireland into Connacht. This led to figures like David O’Dowda being dispossessed of his estates in Sligo and relocating to a smaller estate in Bonniconlon, while Donal O’Dowd was compelled to move to Killeaden. These events ultimately marked the end of the O’Dubhda ownership of territory in Tireragh, lands that had been held by the clan for almost a millennium and a half. Its final destruction as a fortification came in 1690 during the Williamite War, when Lord Granard sacked it and destroyed its defenses, filling the moat and leaving it to ruin.1

The ultimate ruin of Ballymote Castle, a once-mighty Anglo-Norman stronghold, carries a poignant symbolism for the Ó Dubhda clan. While it was never truly “theirs” in the sense of direct ownership, its fate mirrors the broader challenges and eventual decline of independent Gaelic power in Ireland. The castle’s ruined state is not merely decay; it represents the ultimate failure of foreign powers to maintain absolute, unchallenged control over Irish lands. The fact that it was destroyed by Williamite forces in 1690 3, after centuries of being contested, signifies the end of one era of conflict, but also the enduring, albeit transformed, presence of the native Irish. For the Ó Dubhda, who participated in its destruction in 1588 1 and survived the Cromwellian re-conquest 5, the ruin is a monument to their own resilience. It embodies the idea that while structures may fall, the spirit and lineage of the native clans endure. The castle’s transition from a symbol of foreign imposition to a contested prize among Irish clans, and finally to a ruin at the hands of successive English forces, reflects the relentless pressures faced by the clan’s ancestors. Yet, the fact that the clan actively participated in its destruction in 1588, choosing defiance over submission, underscores their enduring spirit and refusal to yield. The castle’s present state, a proud ruin, serves as a powerful reminder of the battles fought and the resilience of the Irish spirit, including that of the Ó Dubhda, who adapted and endured through centuries of profound change.

III. Architectural Marvels: Unveiling Ballymote Castle’s Design

A. The Enduring Strength of its Anglo-Norman Design

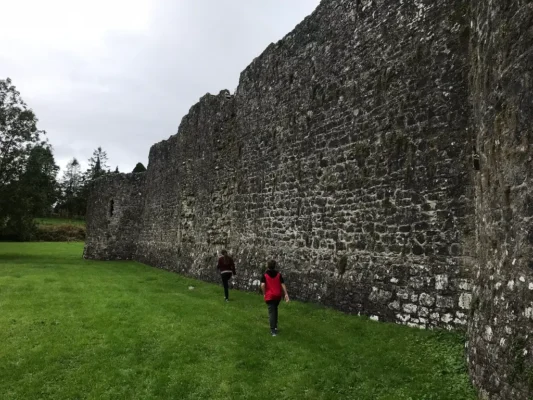

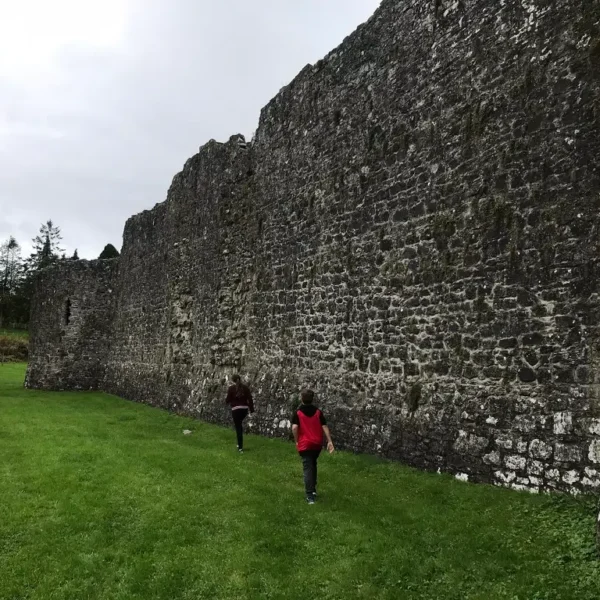

Ballymote Castle, even in its ruined state, remains a testament to formidable medieval engineering. Its design, attributed to Richard de Burgh, drew inspiration from cutting-edge Anglo-Norman fortifications like Beaumaris Castle in Wales.1 The castle is almost square in plan, featuring massive 10-foot-thick walls that speak of its intended impregnability.1 A dominant feature is the rectangular gatehouse on the north wall, flanked by large, projecting half-round towers, designed to protect the primary entrance.1 At the center of the east and west curtain walls stand distinctive D-shaped towers, adding to its defensive capabilities and unique silhouette.1

For the Ó Dubhda, who themselves forged a kingdom “ringed with 20 castles” 5, the architectural prowess displayed at Ballymote would have been both a challenge and a source of strategic study. While their own “10-Pound Castles” often had more ancient origins, built over Stone Age and Bronze Age fortifications 5, Ballymote represented a different scale of defensive architecture. The stark contrast between Ballymote’s Anglo-Norman, concentric design (or at least strong, planned defense) and the Ó Dubhda’s “10-Pound Castles” highlights a significant difference in military architecture and cultural priorities. The Anglo-Normans built to project power and secure conquered territory with massive, engineered fortresses. The Ó Dubhda, while building castles, also emphasized their ancient lineage and connection to the land by often incorporating pre-existing, even prehistoric, fortifications.5 This suggests that while both built defensive structures, their approaches reflected different strategic philosophies and resource bases. Ballymote represents the cutting edge of foreign military technology, while Ó Dubhda castles represent a more organic, deeply rooted, and perhaps adaptable form of defense tied to ancestral sites. Its sheer strength and methodical design would have made any direct assault a daunting prospect, influencing the tactics of resistance, such as the strategic burning in 1588, rather than attempting to hold it. This architectural divergence reflects the broader cultural clash and military asymmetry between the encroaching English/Anglo-Norman power and the indigenous Gaelic clans. It underscores the challenges faced by clans like the Ó Dubhda in defending their traditional ways and lands against a technologically and organizationally different adversary, leading to adaptive strategies like the burning of Ballymote.

B. A Fortress Built for Conflict: Defensive Innovations

Beyond its imposing exterior, Ballymote Castle incorporated advanced defensive features for its time. Internal passages, three feet wide, allowed for rapid movement of defenders along the walls and between towers, a critical advantage during siege.1 The design also included plans for a postern gate on the south wall, though this was never completed, likely due to the castle’s early capture by the O’Connors in 1317.1 All the towers were built taller than the curtain walls, providing superior vantage points and defensive positions.3 A small rectangular tower projecting from the southern curtain wall may have served as a sallyport, allowing defenders to make sudden sorties against besiegers.3

These architectural details underscore the castle’s primary purpose: sustained defense against powerful adversaries. For the Ó Dubhda clan, who were themselves a “maritime power of considerable ability” and adept at holding their territory 5, understanding the strengths and weaknesses of such fortifications was vital. The very existence of Ballymote Castle, with its sophisticated design, shaped the military landscape of Connacht, forcing Gaelic clans to adapt their strategies, whether through direct assault, siege, or, as the Ó Dubhda ancestors demonstrated, through calculated acts of denial like burning the stronghold to prevent its use by the enemy.

IV. Legends and Lore: Tales from Ballymote’s Shadows and Ó Dubhda Echoes

Echoes of Resistance: The Burning of Ballymote – A Clan Memory

While the previous legends speak to the clan’s internal values and mystical connections, the act of burning Ballymote Castle in 1588 serves as a concrete historical event that has taken on legendary status within the clan’s memory. It is a powerful narrative of collective action and defiance. The Ó Dubhda ancestors, standing shoulder to shoulder with the O’Connors and O’Hartes, chose to destroy a formidable English stronghold rather than allow it to be used as a base for further subjugation.1 This act, occurring during a period of intense struggle against the Tudor conquest, embodies the spirit of resistance that defines the clan’s heritage.

This event is not merely a historical footnote; it is a foundational memory that reinforces the Ó Dubhda clan’s active and courageous role in defending Irish sovereignty. It stands as a testament to the ancestors’ strategic thinking and their willingness to make sacrifices for the greater cause of Gaelic freedom. For the clan, the ruins of Ballymote Castle are not just remnants of a bygone era, but enduring monuments to the struggles and triumphs of their people, a constant reminder of their resilience and their unwavering commitment to their heritage.

The “Book of Ballymote”: A Link to the Clan’s Heritage

The “Book of Ballymote” is a major medieval Irish manuscript, a repository of Gaelic learning and history. It is mentioned as preserving a tract on the battle of Damh-chluain, involving Dathi, an ancestor of the O’Dowds.6 While the book was likely compiled

near Ballymote or named for the town, not necessarily the castle itself, its existence and its content (which includes the lineage and tales of the Ó Dubhda ancestors like Dathi) create a powerful symbolic link. That it contains the lineage and tales of the Ó Dubhda 6 means that the very name “Ballymote” is associated with the preservation of the clan’s ancient heritage, even if the castle itself was a foreign imposition. This adds a layer of intellectual and cultural significance to the location, beyond its military history, tying it to the scholarly patronage of clans like the Ó Dubhda, who were patrons of the MacFirbis clan who produced key works like the Great Book of Lecan, another significant manuscript, near Enniscrone in Tireragh, the clan’s territory.5 This connection elevates Ballymote from just a contested fortress to a place intertwined with the intellectual and genealogical preservation of Gaelic identity, further solidifying the Ó Dubhda clan’s deep, multifaceted roots in the region. It shows how the clan’s influence extended beyond military might to intellectual patronage and the safeguarding of historical knowledge.

V. Visiting Ballymote Castle Today: A Glimpse into the Past

A. Location & Access

Ballymote Castle is conveniently located in the market town of Ballymote, County Sligo, Ireland.10 Its address is Carrownanty, Ballymote, Co. Sligo.10 The castle grounds are accessible year-round during daylight hours, and notably, admission is free of charge, making it an inviting destination for all.10

Visitors can reach Ballymote by car, taking the N4 from Sligo Town and then the R293 towards Ballymote, with parking available nearby.10 Public transport options include Bus Eireann services from Sligo Town, with the castle being about a 10-minute walk from the bus stop.10 For those preferring rail, Ballymote train station is also about a 10-minute walk from the castle, offering free 24-hour parking.11

B. What to Expect

Upon visiting Ballymote Castle today, one can expect to encounter an impressive, albeit ruined, Anglo-Norman fortress. Its massive walls, imposing gatehouse, and distinctive towers still convey a sense of its original strength and strategic importance.3 While largely a ruin, it offers a powerful atmosphere for reflection on centuries of history, conflict, and the enduring spirit of the Irish people. The quaint town of Ballymote itself invites exploration, with local shops and eateries available for visitors.10

Visitors, especially those with Ó Dubhda lineage, are encouraged to walk these grounds and contemplate the profound history embedded in the stones. Imagine the Red Earl’s ambition, the struggles of the Gaelic clans for control, and most importantly, the defiant spirit of the Ó Dubhda ancestors who, in 1588, chose to burn this very stronghold rather than see it used against their people. It is a place to connect with the past, to feel the echoes of resistance, and to appreciate the resilience that defines the clan’s heritage.

C. Important Considerations

To ensure a comfortable and respectful visit, it is advised to wear sturdy shoes, as the terrain around a ruined castle can be uneven. While the grounds are open, visitors are asked to respect the historical site and any private property in the vicinity. For a more intimate experience, consider visiting during weekdays or early mornings, especially during the busy summer months.10 As visitors depart Ballymote Castle, they are encouraged to carry with them not just memories of its imposing structure, but a deeper appreciation for the complex tapestry of Irish history and the indelible mark left by clans like the Ó Dubhda. May the spirit of the ancestors’ resilience and their unwavering commitment to their land continue to inspire all.

Conclusion

Ballymote Castle stands as a profound testament to the tumultuous history of Connacht and the enduring spirit of the Ó Dubhda clan. While initially a symbol of Anglo-Norman imposition, its subsequent history of contested ownership among Gaelic clans, and particularly its strategic burning by the Ó Dubhda and their allies in 1588, transformed it into a monument reflecting the ebb and flow of power and the unwavering commitment to Irish sovereignty. The architectural contrasts between Ballymote and the clan’s own “10-Pound Castles” highlight the diverse military and cultural landscapes of the era, underscoring the adaptive strategies employed by the Ó Dubhda in defending their ancestral lands.

Beyond its physical structure, Ballymote’s story is interwoven with the rich tapestry of Ó Dubhda folklore, where tales of honor, justice, and enduring hope—like “The Horse and the Blade” and “The Mermaid of Ard-na-Ree”—serve as powerful repositories of clan values and historical experiences. The very existence of the “Book of Ballymote,” a significant manuscript containing the clan’s pedigree, further links the location to the intellectual and genealogical preservation efforts of the Ó Dubhda. Ultimately, the castle’s ruined state today is not merely an indicator of decay, but a powerful narrative of resilience, symbolizing the failure of foreign powers to maintain absolute control and the survival of Gaelic identity despite centuries of profound change. Ballymote Castle, therefore, is more than just a ruin; it is a proud chronicle of the Ó Dubhda clan’s strategic acumen, their fierce independence, and their deep, multifaceted connection to the land and its history.

Ballymote Castle

Caisleán Bhaile an Mhóta

54.090220°N, -8.520230°W

County Sligo, Ireland

Keepless Enclosure Castle

Anglo-Norman fortification

c. 1300 AD

By Richard de Burgo, Red Earl of Ulster

Never destroyed, fell into ruins

After 1690 (Williamite Wars)

Open daily 9AM-5PM

Access via Ballymote Community Nursing Unit

Located on R296, opposite railway station

The O'Dowds, along with the O'Connors and O'Hartes, sacked the castle in 1588 during English occupation