Ardnaglass Castle

July 10, 2025 2025-07-10 2:28Ardnaglass Castle

Ardnaglass Castle

Sentinel of O’Dowd Legacy and Echoes of Ancient Tales

Ardnaglass Castle, a venerable ruin nestled in the serene landscapes of County Sligo, stands as a poignant testament to centuries of Irish history and the enduring legacy of our powerful O’Dowd clan. Once a vital stronghold within our formidable network of “20 castles,” this site invites visitors to delve into tales of ancient feuds, symbolic acts, and the shifting tides of power that shaped Northwest Connacht. Though time has weathered its stones, Ardnaglass continues to whisper stories of our proud Gaelic lineage, offering a unique glimpse into a complex past where resilience and legend are inextricably intertwined.

I. Overview: Journey Through Time at Ardnaglass Castle

Ardnaglass Castle, located in County Sligo, specifically within the parish of Skreen, is a significant historical site intrinsically linked to our O’Dowd (Ó Dubhda) clan. This castle is recognized as one of the “20 castles” that formed the formidable defensive network of our kingdom in Ui Fiachrach Muaidhe, encompassing what is now modern-day Mayo and Sligo. Even in its current state as a ruin, Ardnaglass serves as a tangible link to our powerful Gaelic lineage that profoundly shaped the history and landscape of the region. It is important to note that Ardnaglass Castle should not be confused with similarly named sites such as Ardgillan Castle or Ardglass Castle, as information pertaining to those locations is not relevant to this O’Dowd stronghold.

The allure of Ardnaglass lies not only in its physical remnants but also in the rich tapestry of history and legend woven around it. The castle’s very existence, even as a weathered ruin, speaks to our clan’s long-term strategic vision and our pragmatic approach to military architecture. Our success in holding our territory intact against formidable adversaries like the Burkes and Birminghams for centuries was intrinsically linked to this robust defensive network. Our clan’s use of diverse stronghold types, including “10-Pound Castles” and adaptations of older ringforts, suggests a well-thought-out and standardized building program, making Ardnaglass a piece of our larger, impressive Gaelic kingdom. This perspective elevates the site from a standalone ruin to a tangible representation of our clan’s enduring power and resilience in a volatile historical landscape.

As a former O’Dowd stronghold, Ardnaglass offers a window into medieval and post-medieval Irish life, showcasing how power was asserted and defended through a network of fortifications. Its current state as a ruin, extant since at least 1786, invites contemplation on the passage of time and the enduring echoes of a vibrant past. The site is particularly notable for its association with compelling local folklore, including the dramatic “Horse and the Blade” feud and the unique tale of “The Dog and the Wolf”.

II. The Storied Past: Ardnaglass Castle Through the Ages

A. Foundations of Power: The O’Dowd Legacy

Ardnaglass Castle was originally built by our O’Dowd (Ó Dubhda) clan, whose roots trace back to the 9th century. Descending in the paternal line from the Connachta’s Uí Fiachrach, we held significant power, serving as Kings of Connacht in the 7th and 8th centuries before becoming the leading sept of the northern Uí Fiachrach, controlling what is now modern-day Mayo and Sligo. Our influence extended beyond military might; we were notable patrons of scholars like the MacFirbises, who produced vital historical works such as the Great Book of Lecan, further cementing our cultural and political authority.

For centuries, we maintained our territory, known as Ui Fiachrach Muaidhe, by encircling it with a formidable defensive network famously described as “20 castles”. Ardnaglass Castle was explicitly identified as one of these crucial strongholds, demonstrating our strategic acumen in holding off powerful forces like the Burkes and Birminghams. While specific construction dates for Ardnaglass are scarce, its inclusion among our “10-Pound Castles” suggests it was a purpose-built tower house or an adapted older fortification, designed for defense against incursions. These castles were key to our territorial control, especially given our significant maritime power in the 12th and 13th centuries.

B. Shifting Hands: From Gaelic Lords to Later Owners

Ardnaglass Castle, initially an O’Dowd possession, later passed into the hands of the MacSweeneys. This transition is particularly significant, as it sets the stage for one of the castle’s most dramatic legends, highlighting the complex and often volatile relationships between clans. Following the Cromwellian re-conquest, the castle’s ownership shifted again, first to the Jones family, with Loftus Jones seated there in 1739 and a Mr. Jones in 1786, and subsequently to the Blacks.

By 1786, Ardnaglass was already referred to as “the ruins of a castle,” indicating its decline from an active stronghold to a historical remnant. By the time of Griffith’s Valuation, the townland of Ardabrone, where the castle is located, was part of the Webber estate, leased by William Graham. Today, the considerable ruins of Ardnaglass Castle are privately owned by Gerry Clarke. The historical narrative of Ardnaglass, marked by these shifts in ownership and its eventual decline into ruin, is not merely a dry chronology. Instead, it is a dynamic interplay of political power, violent conflict, and the rich oral traditions that emerged from these events. The integration of these narratives provides a more vivid and human understanding of the castle’s past, illustrating how historical memory is constructed and preserved through both written records and shared folklore.

To provide a clear overview of these transitions, the following table summarizes the key historical milestones of Ardnaglass Castle:

Period/Date (Approximate) | Key Event/Ownership | Significance |

|---|---|---|

8th-15th Century | O’Dowd Clan Stronghold & Founding | Part of O’Dowd’s “20 castles” defensive network; site of “Dog and Wolf” legend |

15th-17th Century | MacSweeney Possession | Site of major clan feud, “The Horse and the Blade” legend |

Post-Cromwellian (17th-18th Century) | Jones Family Ownership & Transition to Ruin | First documented as ruin; seat of local gentry |

18th-19th Century | Webber Estate Lease | Continued as ruin within larger estate |

Present Day | Current Private Ownership (Gerry Clarke) | Privately owned ruin; adjacent to modern residence |

C. Echoes of Commemoration: The Wolf and the Dog

Beyond the conflicts and ownership changes, Ardnaglass Castle is also associated with a fascinating local legend that speaks to our connection to the land and its challenges. It is said that a dog belonging to our clan heroically killed a wolf that was causing significant damage to flocks in Sligo and Leitrim. This tale underscores the practical concerns and the value placed on acts of protection within the community, highlighting the close relationship between our clan and our environment, and the threats posed by the wild.

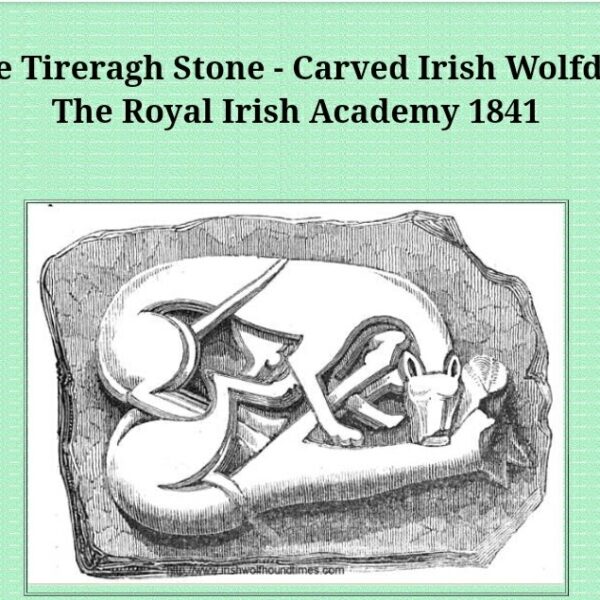

In commemoration of this heroic deed, our ancestors commissioned a stone sculpture depicting the dog killing the wolf. This tangible piece of history, originally from Ardnaglass Castle, was later moved to the Museum in Dublin. This serves as a powerful reminder of our clan’s resilience and our deep-rooted presence in the landscape, highlighting the cultural significance of the castle beyond its military function, showing how important events were memorialized through art.

III. Architectural Marvels: Unveiling Ardnaglass’s Design

A. A Ruined Legacy: Structure and Strategic Context

Ardnaglass Castle today stands as a significant ruin, offering a glimpse into its past grandeur. While specific detailed architectural blueprints of the ruin are not extensively documented, its identity as an O’Dowd castle provides crucial context for its likely form and purpose. The architectural importance of Ardnaglass, in its current ruined state, lies not in its preserved features but in its implied design and strategic purpose within our larger defensive network. The necessity to infer its architecture from our clan’s known building patterns highlights how historical interpretation must often fill gaps using contextual information and broader historical trends. This approach emphasizes the castle’s role as a functional, strategic component of a clan’s power, rather than merely an aesthetic structure.

Our clan was renowned for its adaptable defensive designs, which included traditional Gaelic strongholds like older ringfort sites, adapted Norman castles we had captured, and purpose-built tower houses, often referred to as “10-Pound Castles”. This strongly suggests Ardnaglass conformed to one of these robust, defensible styles, typical of a clan stronghold in medieval and post-medieval Ireland. These “10-Pound Castles” were characterized by their compact, strong design, often built upon sites of ancient strategic importance.

Given its purpose as a clan stronghold within a vital defensive network, Ardnaglass would have been designed with formidable defensive capabilities. Although not explicitly detailed for Ardnaglass itself, castles of the period, including those built by our clan, typically featured thick walls, strategic positioning, and elements like battlements or narrow loop-holes for defense. For instance, a nearby MacSweeney castle was noted for having “a lot of port holes in the wall for shooting out through at their enemies,” indicating common defensive architectural practices in the region. The very nature of a “tower house” implies a vertical, defensible structure designed to withstand sieges, a testament to our commitment to protecting our territory.

IV. Legends and Lore: Tales from Ardnaglass’s Shadows

A. The Horse and the Blade: A Feud Remembered

Legend records a dramatic and chilling turning point in the alliance between the Ó Dubhda (O’Dowd) and Mac Sweeney clans at Ardnaglass. This tale vividly illustrates the volatile nature of clan relationships and the profound impact of perceived dishonor within a hierarchical Gaelic society. It is said that Mac Sweeney, in a deeply disrespectful act, used his wife’s prized horse to carry manure in baskets—an insult that severely wounded her pride and, by extension, the honor of her family, the Ó Dubhda clan. Her prompt message to her brother, the Ó Dubhda chief, ignited his rage, leading to a fateful confrontation.

That very evening, the Ó Dubhda chief visited Mac Sweeney and invited him to walk a stretch of the road home. As they reached Ath na Buaibh, the border between their lands—a place still faintly visible near where Mrs. Mostyn’s house stands today—the O’Dowd turned on his brother-in-law and, in a swift and brutal act, killed him with a sword. This dark tale, etched into the memory of the land, serves as a powerful reminder of alliances forged and shattered, and of how one woman’s indignation could forever alter the fate of two powerful clans. The subsequent ownership of Ardnaglass by the MacSweeneys adds a layer of historical irony and potential lingering tension to this legend, suggesting the long-term repercussions of such a dramatic event.

B. The Dog and the Wolf: A Symbol of Protection

Another significant legend associated with Ardnaglass Castle recounts the bravery of a dog of our clan. This dog is credited with killing a wolf that was causing widespread damage to livestock across Sligo and Leitrim, a testament to the challenges faced by communities in the past and the vital importance of such protective acts. This highlights the close relationship between our clan and our environment, and the threats posed by the wild.

To commemorate this heroic deed, our ancestors commissioned a sculptured stone depicting the dog in the act of killing the wolf. This unique artifact, originally from Ardnaglass Castle, was later moved to the Museum in Dublin. This legend emphasizes our clan’s connection to our land, our people, and our ability to overcome threats, while also providing a tangible link to the castle’s past through a preserved artifact that can still be viewed today. This shows how important events, even those involving animals, were memorialized through tangible cultural heritage.

These two distinct legends offer a multi-faceted understanding of the castle’s significance. “The Horse and the Blade” speaks to the fragility of alliances, the severe consequences of perceived dishonor, and the personal stakes within a hierarchical clan society. Its connection to the MacSweeneys, who later owned the castle, suggests a deep-seated historical animosity or a dramatic power shift. “The Dog and the Wolf” illustrates a different aspect: our clan’s relationship with our environment, our role as protectors of our people’s livelihoods, and how heroic acts were immortalized through material culture. The existence of a physical stone in a museum for “The Dog and the Wolf” elevates this legend from pure folklore to a piece of tangible heritage, inviting further research into its provenance and significance. Together, these legends paint a vivid picture of the human and natural challenges faced by our clan and how these were processed and remembered through narrative, demonstrating that folklore is a crucial lens for historical understanding.

V. Visiting Ardnaglass Castle Today: A Glimpse into the Past

A. Location & Access

Ardnaglass Castle is located in County Sligo, within the parish of Skreen. More specifically, it is situated just off the Coast Road on Protestant Lane. The ruins are adjacent to a modern bungalow in the townland of Ardabrone.

It is crucial for potential visitors to understand that Ardnaglass Castle is a ruin located on private land, currently owned by Gerry Clarke. While its proximity to a bungalow and Dunmoran Beach (a 10-minute walk) might suggest easy access, visitors must respect the private nature of the property. The area immediately surrounding the bungalow is described as a “private area where you can enjoy the fresh air and surrounding natural beauty,” implying that casual, unannounced visits to the immediate castle site might not be appropriate. Direct access to the ruins may require prior permission from the landowner. As a privately owned ruin, there are no official opening hours or admission fees. Access would be dependent on the landowner’s discretion and respectful inquiry. Visitors should assume it is not a publicly managed heritage site with regular public access.

B. What to Expect

Visitors to Ardnaglass Castle should expect to encounter the “considerable ruins” of a historical stronghold. The experience will be one of atmospheric contemplation, imagining the past lives lived within these weathered stones. It is a place to connect with history through its physical remnants and the powerful legends associated with it, rather than a restored or fully accessible structure. The ruins offer a quiet, reflective space to appreciate the passage of time and the enduring echoes of a vibrant past. The castle ruins are set amidst the scenic County Sligo landscape, adjacent to a private residence and within walking distance of Dunmoran Beach. This offers opportunities to combine a historical visit with appreciation of the natural coastal beauty, making it part of a broader exploration of the area.

C. Important Considerations

The status of Ardnaglass as a privately owned ruin directly dictates the visitor experience. Unlike major tourist attractions, it lacks formal infrastructure such as official opening hours, admission fees, or guided tours. The phrase “private area where you can enjoy the fresh air and surrounding natural beauty” regarding the adjacent bungalow underscores that the primary use of the land is private, not public tourism. This highlights a common challenge for many historical sites in Ireland: their integration into modern private land ownership. The castle’s preservation and public accessibility are largely dependent on the private owner’s discretion, rather than state or organizational bodies. This necessitates a shift in the visitor’s mindset from “visiting a destination” to “experiencing a historical landscape with respect for its current context and the rights of private property owners.”

The most important consideration is to always respect private property. Visitors should seek permission from the landowner (Gerry Clarke) before attempting to access the immediate vicinity of the ruins. Unauthorized access is strongly discouraged and can be considered trespassing. As a ruin, the site may present hazards such as uneven ground, unstable structures, or hidden debris. Visitors should exercise extreme caution, wear sturdy footwear, and be mindful of their surroundings. Finally, responsible tourism dictates leaving no trace. Any visit should be conducted with utmost respect for the historical site, the surrounding environment, and the privacy of local residents. Disturbing archaeological features or removing artifacts is strictly prohibited.

VI. Further Reading & Credits

Further Reading

For those wishing to delve deeper into the history of Ardnaglass Castle, our O’Dowd clan, and related topics, several resources are available:

O’Dowd Clan History: For comprehensive information on our O’Dowd clan and our broader network of castles, the

odubhda.org/castles/resource and the Wikipedia entry on O’Dowd are invaluable. These provide context on our rise to power, our defensive strategies, and our cultural patronage, essential for understanding Ardnaglass’s place within the larger O’Dowd legacy.Local History and Folklore: The Duchas.ie resource offers unique local perspectives and legends, particularly the tale of “The Dog and the Wolf,” which adds a rich, localized layer to Ardnaglass’s story.

Landed Estates Database: The Landed Estates database from the University of Galway provides crucial details on the castle’s later ownership and its status as a ruin from the 18th century onwards, offering a glimpse into its post-Gaelic history.

The report’s content is derived from a diverse range of sources, including academic and genealogical records, local folklore, clan-specific websites, and even contemporary real estate listings for current status. Each source type contributes a unique piece to the puzzle. Genealogical records provide lineage and broad historical context; local folklore preserves community memory and specific narratives; academic databases track land ownership and historical status; and contemporary information offers crucial details about current accessibility and private ownership. This demonstrates that a complete and nuanced historical understanding of a site like Ardnaglass, especially one that is a ruin with fragmented records, cannot be achieved through a single type of source. The synthesis of these disparate sources is crucial for building a robust and compelling narrative, highlighting the inherent challenges of historical research when dealing with fragmented or indirect evidence, and emphasizing the need for comprehensive and critical evaluation of all available information.

Credits and Acknowledgements

Information for this report was compiled from various historical and archaeological sources, including:

Wikipedia: O’Dowd

Duchas.ie: Local folklore and history

Landed Estates Database, University of Galway

Daft.ie property listing

Wikipedia: Skreen

Special acknowledgement is extended to the O’Dubhda clan for preserving and sharing their rich heritage and to the local communities whose oral traditions keep these stories alive.

Conclusion

Ardnaglass Castle, though now a ruin, remains a powerful symbol of our clan’s enduring legacy and our significant role in shaping the history of Northwest Connacht. Its story is one of strategic foresight, as evidenced by its place within a formidable network of fortifications designed to protect our thriving Gaelic kingdom. The castle’s architectural significance, while largely inferred from its context as an O’Dowd stronghold, speaks to the pragmatic and robust defensive designs employed by our clan.

Beyond its physical remnants, Ardnaglass is imbued with compelling narratives. The dramatic “Horse and the Blade” legend vividly portrays the volatile nature of inter-clan relations and the profound impact of honor and vengeance. In contrast, “The Dog and the Wolf” legend, with its tangible stone monument now in a museum, highlights our clan’s connection to our land and our role as protectors. These tales are not mere folklore; they are vital cultural markers that offer a deeper understanding of the values, challenges, and historical memory of our people.

The current status of Ardnaglass Castle as a privately owned ruin underscores the evolving relationship between historical sites and modern land use. While it presents challenges for public access, it also invites a more respectful and contemplative form of engagement, urging visitors to appreciate the site’s history while honoring the privacy of its current custodians. Ardnaglass Castle stands as a testament to a powerful past, its weathered stones and whispered legends continuing to offer a profound glimpse into a vibrant and resilient Gaelic heritage.

Ardnaglass Castle

Ard na gClois (Height of the Noises)

54°15'21.9"N, 8°42'24.6"W

Ardabrone townland

Near Skreen, County Sligo, Ireland

Tower House

Likely part of a standardized defensive network of 10-pound castles

c. 13th–15th century (by O'Dubhda clan)

Exact date unconfirmed; part of O'Dowd network of 20 castles

Ruined by 1786

Result of clan feuds, shifting ownership, and Cromwellian re-conquest

Currently a significant ruin on private property

Located in an active cow field

Not publicly accessible – bulls present

Use extreme caution and do not enter without landowner permission

Accessible only from road with caution — do not enter field without permission

Built and maintained by the O'Dubhda clan

One of 20 castles in their defensive network

Later involved in inter-clan conflict with the MacSweeneys

Associated with key legends such as "The Horse and the Blade" and "The Dog and the Wolf"

Ardnaglass Castle stands as a haunting echo of O'Dubhda resilience and strategy. It serves not only as a ruined stronghold, but also as a portal into clan alliances, feuds, and heroic legends that shaped the heritage of Northwest Connacht.